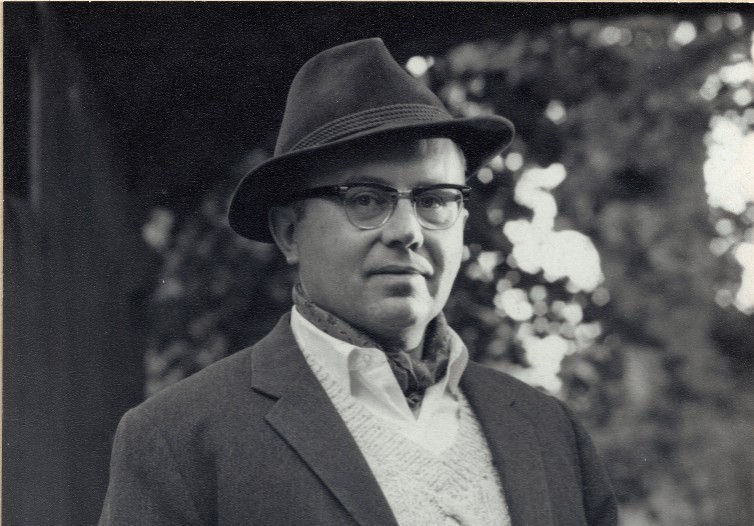

The following passage is excerpted from Russell Kirk's Redeeming the Time and was recently published in this format in the Intercollegiate Review (original article).

Our term “liberal education” is far older than the use of the word “liberal” as a term of politics. What we now call “liberal studies” go back to classical times; while political liberalism commences only in the first decade of the nineteenth century. By “liberal education” we mean an ordering and integrating of knowledge for the benefit of the free person—as contrasted with technical or professional schooling, now somewhat vaingloriously called “career education.”

The idea of a liberal education is suggested by two passages I am about to quote to you. The first of these is extracted from Sir William Hamilton’s Metaphysics:

Now the perfection of man as an end and the perfection of man as a mean or instrument are not only not the same, they are in reality generally opposed. And as these two perfections are different, so the training requisite for their acquisition is not identical, and has accordingly been distinguished by different names. The one is styled liberal, the other professional education—the branches of knowledge cultivated for these purposese being called respectively liberal and professional, or liberal and lucrative, sciences.

Hamilton, you will observe, informs us that one must not expect to make money out of proficiency in the liberal arts. The higher aim of “man as an end,” he tells us, is the object of liberal learning. This is a salutary admonition in our time, when more and more parents fondly thrust their offspring, male and female, into schools of business administration. What did Sir William Hamilton mean by “man as an end”? Why, to put the matter another way, he meant that the function of liberal learning is to order the human soul.

Now for my second quotation, which I take from James Russell Lowell. The study of the classics, Lowell writes, “is fitly called a liberal education, because it emancipates the mind from every narrow provincialism, whether of egoism or tradition, and is the apprenticeship that everyone must serve before becoming a free brother of the guild which passes the torch of life from age to age.”

To put this truth after another fashion, Lowell tells us that a liberal education is intended to free us from captivity to time and place: to enable us to take long views, to understand what it is to be fully human—and to be able to pass on to generations yet unborn our common patrimony of culture. T. S. Eliot, in his lectures on “The Aims of Education” and elsewhere, made the same argument not many years ago. Neither Lowell nor Eliot labored under the illusion that the liberal discipline of the intellect would open the way to affluence.

So you will perceive that when I speak of the “conservative purpose” of liberal education, I do not mean that such a schooling is intended to be a prop somehow to business, industry, and established material interests. Neither, on the other hand, is a liberal education supposed to be a means for pulling down the economy and the state itself. No, liberal education goes about its work of conservation in a different fashion.

I mean that liberal education is conservative in this way: it defends order against disorder. In its practical effects, liberal education works for order in the soul, and order in the republic. Liberal learning enables those who benefit from its discipline to achieve some degree of harmony within themselves. As John Henry Newman put it, in Discourse V of his Idea of a University, by a liberal intellectual discipline, “a habit of mind is formed which lasts through life, of which the attributes are freedom, equitableness, calmness, moderation, and wisdom; of what…I have ventured to call the philosophical habit of mind.”

The primary purpose of a liberal education, then, is the cultivation of the person’s own intellect and imagination, for the person’s own sake. It ought not to be forgotten, in this mass-age when the state aspires to be all in all, that genuine education is something higher than an instrument of public policy. True education is meant to develop the individual human being, the person, rather than to serve the state. In all our talk about “serving national goals” and “citizenship education”—phrases that originated with John Dewey and his disciples—we tend to ignore the fact that schooling was not originated by the modern nation-state. Formal schooling actually commenced as an endeavor to acquaint the rising generation with religious knowledge: with awareness of the transcendent and with moral truths. Its purpose was not to indoctrinate a young person in civics, but rather to teach what it is to be a true human being, living within a moral order. The person has primacy in liberal education.

Yet a system of liberal education has a social purpose, or at least a social result, as well. It helps to provide a society with a body of people who become leaders in many walks of life, on a large scale or a small. It was the expectation of the founders of the early American colleges that there would be graduated from those little institutions young men, soundly schooled in old intellectual disciplines, who would nurture in the New World the intellectual and moral patrimony received from the Old World. And for generation upon generation, the American liberal-arts colleges (peculiar to North America) and later the liberal-arts schools and programs of American universities, did graduate young men and women who leavened the lump of the rough expanding nation, having acquired some degree of a philosophical habit of mind.

You will have gathered already that I do not believe it to be the primary function of formal schooling to “prepare boys and girls for jobs.” If all schools, colleges, and universities were abolished tomorrow, still most young people would find lucrative employment, and means would exist, or would be developed, for training them for their particular types of work. Rather, I believe it to be the conservative mission of liberal learning to develop right reason among young people.

Not a few members of the staffs of liberal-arts colleges, it is true, resent being told that theirs is a conservative mission of any sort. When once I was invited to give a series of lectures on conservative thought at a long-established college, a certain professor objected indignantly, “Why, we can’t have that sort of thing here: this is a liberal arts college!” He thought, doubtless sincerely, that the word “liberal” implied allegiance to some dim political orthodoxy, related somehow to the New Deal and its succeeding programs. Such was the extent of his liberal education. Nevertheless, whatever the private political prejudices of professors, the function of liberal education is to conserve a body of received knowledge and to impart an apprehension of order to the rising generation.

Comments